Earlier this year, the third largest supermarket chain in France Intermarche released a global campaign to sell the non-calibrated and “imperfect” fruits and vegetables that industries usually throw away due to their unpresentable appearance. In a declared attempt to address food waste, Intermarche renamed these underdogs to “Inglorious Fruits and Vegetables” and advertised them in print, billboards, TV, radio, PR, Intermarche’s catalogues and social media. The Inglorious Fruits and Vegetables were sold 30% cheaper than regular produce. The supermarket chain then had a 300% increase of mentions on social networks during the first week, 1.2 tons average sale per store during the first two days, and an additional 24% of overall store traffic.

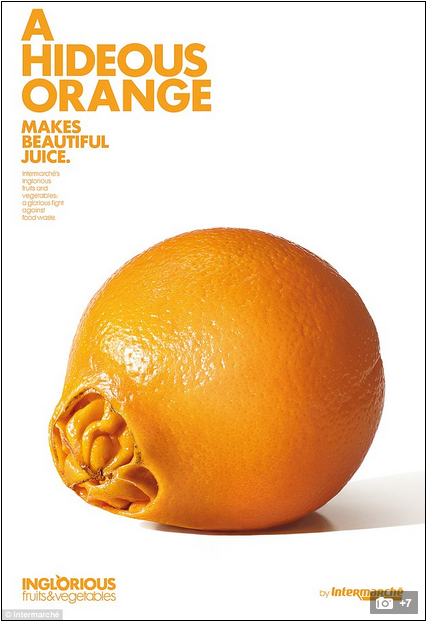

Semiotics suggests that meaning is not fixed and is socially constructed. In this instance, pleasing appearance has been correlated with good quality, as deformity is to dysfunction. In fact, people initially underestimated fruits and vegetables that deviated from the standard produce in supermarkets, especially the high-end supermarkets that guarantee quality. But then, they began to buy out the substandard fruits and vegetables when they were presented as the endearing Inglorious Fruits and Vegetables. Intermarche managed to turn the deviant fruits and vegetables into something attractive by endowing them with big words (i.e. “grotesque” and “hideous”), self-depreciating humor and minimalist presentation favored by the French.

The saying about human physical appearance that “looks don’t matter and what matters is what is on the inside” proved to be applicable to the inanimate fruits and vegetables. Intermarche apparently wanted to convey this idea by selling delicious Inglorious Fruit Juices and Inglorious Vegetable Soups. Their video advertisement mentions that this strategy meant to prove to people that the Inglorious Fruits and Vegetables were just as good as the “normal” fruits and vegetables.

Advertising has been said to be effective not just when people notice an advertisement, but when they change their behavior in line with the ideas asserted by the advertisement. The Intermarche campaign apparently succeeded in these terms, as it was able to reshape the public’s perspective about lumpy and misshapen fruits and vegetables.

From a Marxist point of view, we see how the elite determine what is beautiful (or desirable) and worth consuming. In fact, the appeal of the Inglorious Fruits and Vegetables comes from how they are attributed with elite qualities such as the vocabulary used in captions and artistic presentation in posters. At surface level, we can appreciate Intermarche’s intention of preventing food waste. It indeed convinced people to take disfigured fruits and vegetables into consideration. But then again, one may begin to ask if it was more about profit upon realizing a few things.

First, the campaign increased business for Intermarche. The Inglorious Fruits and Vegetables campaign implied that the market would only stop throwing food away if people would buy it. In fact, five of Intermarche’s main competitors launched a similar offer probably not only because they saw it as an effective way to get people to help prevent food waste, but because the markets saw commercial potential in Intermarche’s prior success. For at least some of the companies, it was a gimmick that would attract more customers.

Second, the campaign may have had a counterproductive effect on standard fruits and vegetables. With Poststructuralism in mind, the Inglorious Fruits and Vegetables was an instance of the “ugly” subverting the favored “beautiful.” In supermarkets, the Inglorious Fruits and Vegetables were given their own aisle, own space on the receipt, and own label. This leaves us wondering if the sudden favor leaning towards such fruits and vegetables left the “normal” ones neglected and therefore wasted. If this is true, then the campaign did not resolve the problem of food waste. It merely inverted the binary opposition with the standard fruits and vegetables as the new surplus.

Lastly, people bought the Inglorious Fruits and Vegetables because of the branding attached to them. It is uncertain to say whether the campaign made people change their minds about misshapen fruits and vegetables in general, regardless of their label. Perhaps companies would not even dare sell deformed fruits and vegetables in bulk if they were not accompanied with a campaign as appealing as the Inglorious Fruits and Vegetables.

References:

Cliff, Martha. “Forget the Ugli Fruit, Meet the Ugly Fruit Bowl! French Supermarket Introduces Lumpy and Misshapen Fruit and Vegetables – Sold at a 30% Discount – to Combat Food Waste.” Mail Online. July 18, 2014. Accessed November 15, 2014. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/food/article-2693000/Forget-ugli-fruit-meet-ugly-fruit-bowl-French-supermarket-introduces-lumpy-misshapen-fruit-vegetables-sold-30-discount-combat-food-waste.html.

“Inglorious Fruits & Vegetables.” Intermarché – Inglorious Fruits & Vegetable. Accessed November 15, 2014. http://itm.marcelww.com/inglorious/.